At the beginning of the decade, we still lived in a pre-Ellen and pre-Will-and-Grace world. There was still great stigma attached to being LGBTQ. And the ignorant blamed us for the AIDS crisis, all evidence to the contrary. The BGMC was well prepared now to take on these fights.

The new decade did not begin easily for the chorus; indeed it was one of the most tumultuous years the chorus had ever faced. The stressors of being a political, social, and artistic organization continued to cause conflict within the organization. Should we change pronouns from the original to suit our gay identity? Should we sing music by composers tied to Nazi Germany? Should our program advertising be sanitized so as not to offend our audience members? And, of course, the never-ending debate about the balance of traditional classical and popular music in the chorus’ repertoire.

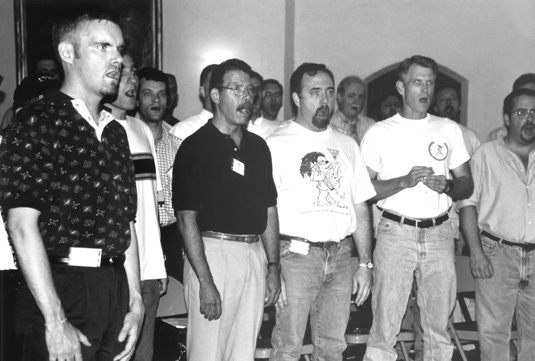

This year, however, the conflict was large and dramatic. Many members were vocally unhappy, especially about repertoire. We almost lost Robert Barney. And we did lose 20 members, representing a full 20% of the membership at the time. Robert and Bob Ebersole were interviewed by the Boston Globe shortly after the tumult ended, just prior to the spring concert in March 1991. From the interview:

“It’s a circle, really,” Barney says, “and everyone enters it at a different place, and one aspect or another is more important to each member than the others, but all three things are important to everybody. I spent a lot of time unsuccessfully trying to make everybody happy all of the time. That’s never going to happen. There will always be conflicts about whether to do more or less classical music or to sing in foreign languages; if these conflicts are alive, it means we are doing it right. We’ve been through the bad time of confusion over what the chorus is all about, and now we’re on our way forward again.”

Barney and Ebersole also point out that the very existence of the chorus makes a political statement. “The fact we’re listed in the phone book, the fact that people write checks to buy tickets or to support our work is in itself a political statement. It is not the same thing for a gay singer to perform with the Handel & Haydn Society or another chorus; one point of our chorus is its visibility, and one of the reasons our members join is that they want to be visible.”

Robert spoke to the importance of the chorus to the members, not just in terms of music and performing, but in their overall lives:

The social importance of a gay chorus goes far beyond the brunch and party circuit; for some members the chorus becomes an extended family. “Time after time,” says Barney, “I have seen singers about to go onstage for their first concert, terrified, the first time they were going out to perform as an openly gay person. But by intermission time they were welling up with excitement, and before long they were inviting their families, friends and their boss; the chorus has played an important part in their lives. It certainly did in mine: I was the organist and choir director in a church, and when I applied for this job, I told them I was going to, and they were totally supportive. When I left to go to another church, this job was on my resume.”